Why Indoor Environments Matter More Than Ever at COP30

At the annual global stage of climate governance—COP30—the negotiation table is filled with some of the world’s most complex issues. Yet, as environmental engineer Kerry Kinney emphasizes, the “context” in which people think and decide is often ignored: air quality, lighting, temperature, humidity, and overall indoor comfort.

Seemingly minor indoor environmental details can, in reality, quietly shape the outcome of high-stakes talks.

Indoor Air: The Invisible Factor That Shapes Thinking Quality

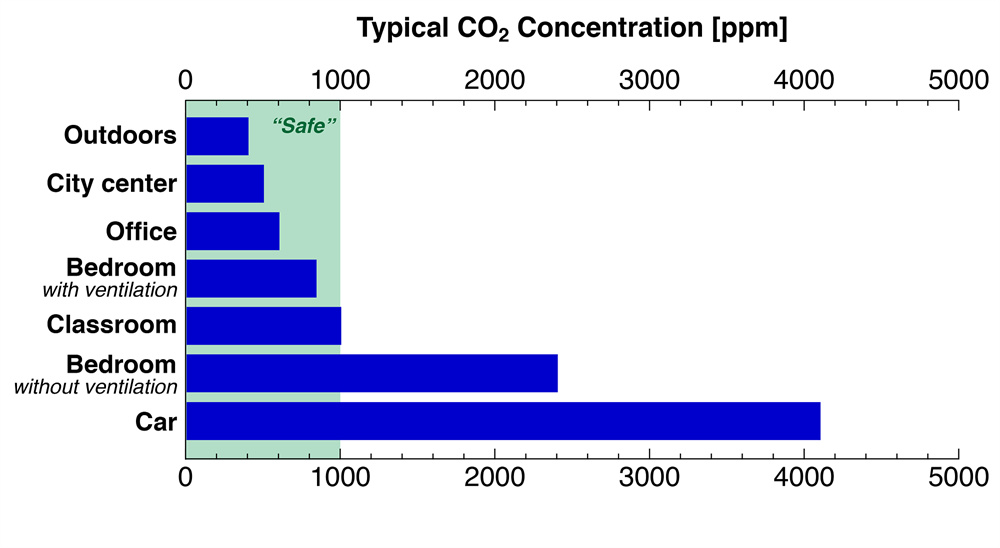

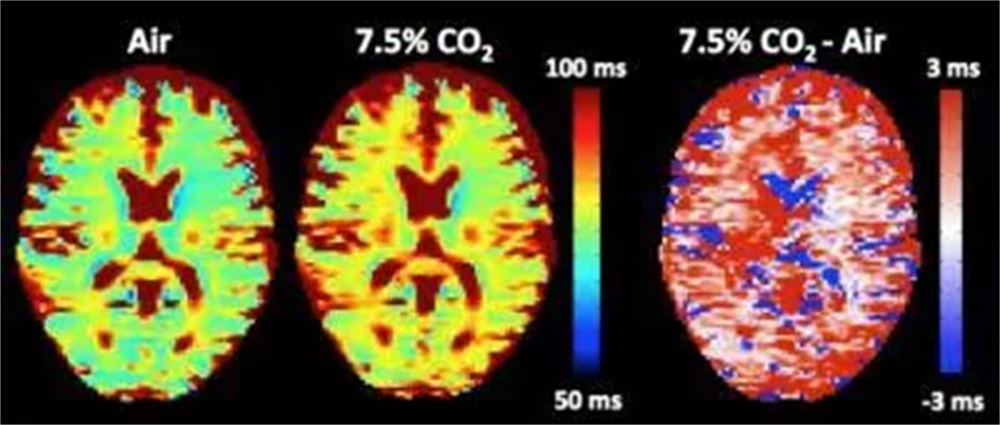

Kinney points out that once indoor air becomes stuffy and carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels rise, people’s ability to think clearly starts to decline. Research shows that even a moderate increase in indoor CO₂—around 1,000–2,000 ppm—can reduce concentration and slow decision-making.

At COP30, meeting spaces are often crowded, enclosed and inadequately ventilated. With long sessions and high occupant density, CO₂ levels can easily climb into ranges known to affect cognitive performance.

She underscores how temperature, humidity, air quality and light all influence how people feel and function, and how the quality of decisions is closely tied to these physical and mental states. In other words, the “room conditions” are not just a backdrop; they form part of the decision-making infrastructure.

Meeting rooms with clean, fresh air, comfortable temperatures, balanced humidity and well-designed lighting help participants stay alert, focused and more capable of working through complex policy challenges.

How CO₂ Affects the Human Body: From “Harmless” to “Cognition-Changing”

Carbon dioxide is a colorless, odorless gas that humans cannot directly sense. Indoors, the most common source of CO₂ is human breathing. When people exhale, they release CO₂ as a natural byproduct of metabolism.

In enclosed or poorly ventilated spaces, especially where many people gather, CO₂ accumulates quickly. Over time, rising CO₂ displaces oxygen in the air and can begin to affect how people feel and think.

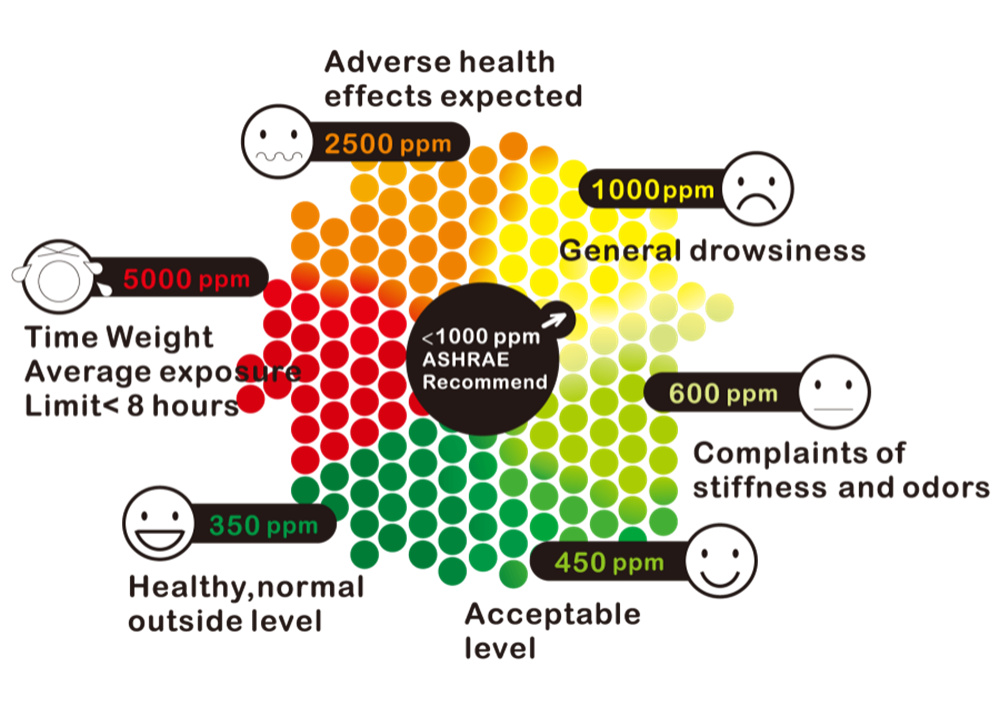

Typical indoor CO₂ ranges and their effects:

- ● 400–1,000 ppm (Normal range)

Indicates good ventilation and steady air exchange. People can think clearly with minimal impact from CO₂, and the indoor environment generally feels fresh. - ● 1,000–2,000 ppm (Mild effects)

CO₂ begins to cause noticeable symptoms as oxygen is gradually displaced. Common effects include sleepiness, a sense of stuffiness, mild confusion and feeling slightly disoriented. This range is commonly reached in busy meeting rooms or classrooms without adequate fresh air. - ● 2,000–5,000 ppm (Moderate effects)

Higher levels can lead to headaches, pronounced drowsiness, chest tightness, faster heart rate, reduced attention and difficulty focusing. At this level, cognitive performance and decision quality can be significantly undermined, particularly in long meetings.

Research indicates that even short-term exposure to moderate CO₂ elevations can negatively impact performance on complex tasks, strategic reasoning and problem-solving. For a high-pressure environment like COP30, where negotiations depend on sustained attention and nuanced judgment, this invisible factor can be consequential.

The Real-World Challenges of COP30: Enclosed Spaces, Harsh Light and Stacked Stress

The reality of COP30 is that many events are hosted in temporary or repurposed structures. Some areas suffer from poor ventilation, harsh artificial lighting, confusing layouts and constant background noise.

These physical conditions layer on top of other stressors:

- ● Jet lag and fatigue after long-haul flights

- ● High psychological pressure to deliver outcomes within a fixed deadline

- ● Dry indoor air and glaring lights

- ● Increased risk of respiratory infections at large gatherings

Taken together, the physical and emotional stressors make indoor environmental quality an often overlooked variable that can influence the pace and quality of climate negotiations.

Kinney and other experts suggest that ideal negotiation spaces should offer:

- ● Ample natural light

- ● Stable and comfortable temperature and humidity

- ● Reliable access to fresh outdoor air

- ● Real-time monitoring of key indoor air parameters such as CO₂

- ● Calm, well-organized layouts that reduce confusion and noise

In this view, indoor air is not merely a comfort feature, but a core element in enabling clear thinking, collaboration and effective problem-solving.

Improving Indoor Air: Simple Technology, Significant Impact

Improving the indoor environment at a large conference like COP30 does not necessarily require radical redesigns. Some of the most impactful measures are also the most straightforward.

1. Increase Fresh Air Ventilation to Dilute CO₂

Bringing in sufficient outdoor air is the primary way to reduce indoor CO₂ levels. This also helps lower the concentration of airborne pathogens and other indoor pollutants.

2. Use Efficient Mechanical Ventilation Systems

Modern HVAC and ventilation solutions can monitor indoor CO₂, particulate matter and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in real time, automatically adjusting airflow and filtration to maintain healthy conditions.

You can explore a range of professional ventilation and fresh air systems here:

https://www.airwoods.com/airwoods-eco-pair-1-2-wall-mounted-single-room-erv-60cmh35-3cfm-product/

3. Design Healthier Indoor Lighting

Access to natural light or carefully designed artificial lighting supports circadian rhythms, reduces eye strain and helps alleviate fatigue, all of which contribute to better communication and decision-making.

4. Implement Real-Time Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) Monitoring

By tracking CO₂ and other indicators, organizers can respond quickly to rising levels, increase ventilation when necessary and prevent prolonged exposure to poor air quality.

In Climate Negotiations, “Air Quality” Is Part of the Negotiation Itself

The complexity of COP30 is not only rooted in the climate agenda itself, but also in the conditions under which people attempt to resolve it. Indoor environments shape how participants feel, think and collaborate.

When people feel alert, comfortable and physically well, the quality of their discussions and decisions improves. Good air quality may be one of the simplest—and most underestimated—levers for supporting better outcomes.

Responding to climate change requires global cooperation. The quality of that cooperation starts with something as fundamental as the air everyone shares in the room.